You Can't Outrun Trauma (and benzos won't help either)

Teaching was my dream job. Words cannot describe the satisfaction it gave me. The more I poured into it, the more I received. I made it my goal to cultivate my students’ enthusiasm, curiosity, understanding, talents, and skills. I watched them develop with such pride and joy.

To say I went above and beyond would be an understatement. I was the kind of teacher who spared no effort and no personal expense. My classroom was a welcome oasis, designed to spark any child’s imagination with dozens of plush puppets, cozy bean bag chairs, books, and games galore. During weekends and holidays, I was painting sets, choreographing routines, sewing costumes, writing scripts, or editing footage. For several years, the front page of our local newspaper featured my students all decked out in their Shakespeare costumes, beaming at the camera. We’d also make video parodies to whatever pop songs were all the rage. I’d smile when I’d overhear them saying things like “I can’t believe I’m in the news!” or “Mrs. Granger made us famous on YouTube!”

Yet, there was a dark side to all of this so called “success”. At the time, I couldn’t understand what motivated me to be a super teacher. I never really saw it clearly until everything fell apart. The truth was that I was a chronic overachiever because I was trying to outrun my childhood trauma. It turns out you can’t just put it behind you.

My therapist was forever trying to get me to slow down. “Beth, they are only primary students. All you must do is teach them the basics. Why don’t you aim to be a mediocre teacher?” That advice made my skin crawl. I couldn’t even comprehend lowering my expectations. There is no way I could be mediocre. I wouldn’t be safe.

Safe from what? Only hindsight has given me the answer.

I was desperate for validation after years of being told I was a worthless sinner. That I was nothing without God. That if I broke my lifelong vows of obedience to our leaders, I’d be a streetwalker or go straight to Hell.

Less than a year after I escaped, I landed a full-time teaching contract at my first interview. At that point, I still had no clue that I’d spent my first three decades in a cult. All I knew was that I was deeply unhappy and couldn’t uphold my vows any longer. I left because I felt too sinful, not because the place was abusive.

It would take me decades to comprehend the full truth. Why I could never feel at ease. Why I constantly felt like I was in front of a panel of judges. Why I imagined I’d be publicly humiliated at every turn. Why I could sense the criticism of my bosses and colleagues like a forcefield.

Apart from keeping up appearances, I couldn’t even tolerate the idea of slowing down. I found that if I constantly operated on high speed, I could keep the voices at bay. Over time, I could no longer distinguish between the voices of my abusers and my own inner critic. They had morphed together into one hideous, frightful being that tormented me day and night.

It turns out that you can’t outrun those voices. Or the traumatic memories, long buried. Cracks appeared soon after I landed my dream job. For one thing, I couldn’t stop bingeing. Desperate to fix my eating, I sought therapy. Soon, it became apparent that I needed a psychologist and a psychiatrist.

To help cope with the demands of teaching and parenting, I was prescribed all kinds of meds. Most of them had intolerable side effects. We finally landed on a benzodiazepine called Ativan. At first, it took the edge off my crushing anxiety. After a while, it didn’t seem to be doing anything, but I figured it couldn’t hurt to keep taking it as prescribed.

Biggest mistake of my life.

I took three Ativan per day for nearly ten years. It took a long time for me to notice that I was losing my short-term memory. I was forgetting everything. My students’ names, what I had taught the day before, the million things I needed to manage simultaneously.

It was so bad, that I finally googled the problem. My heart would race as I skimmed through articles warning the risks associated with long-term use of benzodiazepines:

Those who had taken a benzodiazepine for more than six months had an 84% greater risk of developing Alzheimer's than those who hadn't taken one. (Merz, 2014, Harvard Health Publishing)

Benzodiazepines generally should not be prescribed continuously for more than one month. (Johnson, 2013, American Family Physician)

Even for younger people, benzodiazepines cause acute cognitive impairment. Increased risk of dementia is another major concern with long-term use of benzodiazepines. (McKeehan, 2016, Cognitive Vitality)

Why didn’t I do my research? I thought, panicking. I’d been under the impression that I’d be on Ativan for the rest of my career, which was another decade. Could I handle teaching without meds?

My psychiatrist advised that I taper off slowly by cutting back one pill every two months. Feeling hopeful (and a little fearful), I resolved to spend the rest of my life med-free.

The first few days after the first taper weren’t so bad. I felt weird, and kind of disoriented. I can handle this, I kept telling myself.

Within a week, though, I felt like a human possessed. My anxiety was so acute that my skin felt like it was crawling, and my muscles were involuntarily clenching. I couldn’t stand to be around my beloved students. It felt like they were an infestation of rats, all clawing at me simultaneously. One morning in February, I snapped. Tears streaming, I ran to the office and begged the principal to cover my class. He kindly obliged and told me to take the rest of the day off. I couldn’t possibly conceive of the journey that awaited me as I left his office.

My symptoms were so severe that I called my psychiatrist for an emergency appointment. I told her what I was experiencing: heart palpitations, the inability to catch my breath, panic attacks, persistent vertigo, crying over everything, and much more. I also told her how the simplest tasks were overwhelming me. How I was so dizzy that I was falling over. How I couldn’t concentrate on anything or form coherent sentences. How I’d lost the desire to do anything, even things I enjoyed.

My psychiatrist ordered me off work until the end of June. I couldn’t imagine being off work for so long. But I didn’t argue. Something was terribly wrong, and I couldn’t possibly handle working.

My first thought was, I’ll take this time off to get healthy! I’ll have time to exercise and maybe I’ll finally stop bingeing and lose weight! I was so clueless.

Over the next few months, my symptoms got worse. I could barely function. I couldn’t speak without taking long pauses to find words that would never come to me. I couldn’t handle reading—not only books, but also social media posts and even recipes. Using a computer was also out of the question. Even checking email overwhelmed me.

One day, I experienced a panic attack while driving on the highway. My daughter was in the car with me, and I’d already been driving for 40 minutes. Suddenly, I felt like I couldn’t breathe, and started gasping for air, like I was hyperventilating. Alarmed, my daughter grasped my hand and held on tight. Then the tunnel vision began. Terrified, I felt like my car was going at Mach speed and was about to crash. Fear gripped me, and I started scream crying. “I’m so scared! I can’t do this! Oh God! Oh God!”

After what seemed like an eternity, I pulled over at the side of highway 401. Pulse galloping, I got out of the car and tried to catch my breath. But as soon as I pulled back onto the highway, the symptoms returned with a vengeance. I barely made it to the next exit.

This kind of panic would happen every time I attempted highway driving. It got so bad that I couldn’t even handle merging into traffic. For well over two years, I would avoid highways altogether.

Another withdrawal symptom I couldn’t stand was “akathisia,” or the constant urge to move. I felt a persistent restlessness that propelled me to want to pace, rock while standing, or clench my muscles. Often, I pictured my body undergoing a Hulk-like transformation. It felt like every muscle was exploding. As a result, “resting” was out of the question. The only thing that provided relief was aggressive exercise. But the loud fitness classes I’d once loved now overwhelmed my senses. So, I took to walking. No matter the weather, I’d head out for an hour-long walk, at least twice a day. I walked so much that within a year, I developed chronic foot and knee pain.

Eventually, I joined a few Facebook groups for people going through benzo withdrawal. It helped to know I wasn’t alone. I also learned that tapering is dangerous and that I should have done it more slowly. Many people never manage it. On top of the symptoms I was already experiencing, benzo withdrawal can cause life-threatening symptoms like seizures, suicidal thoughts, and psychosis. And when you taper too quickly, you can experience protracted withdrawal symptoms that can last for years. Worst of all, most doctors and even psychiatrists aren’t aware of the dangers of benzo use and withdrawal.

Almost five years have passed since my last day of teaching. During this time, not only did I battle the effects of withdrawal, and my insurance company (who denied me long term disability), but I battled my abusers at the Ontario Superior Court of Justice. I was a representative plaintiff in a landmark class action that took 16 years to resolve. We sued our cult leaders and became the first historical abuse case to win at trial in Canada. (But that’s another story!)

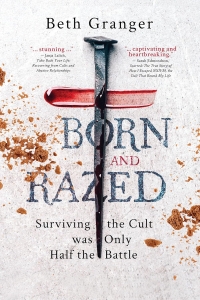

Above all, I finally faced my trauma head on. Without the distractions of a career, I could no longer avoid it. I sat still, I walked, I journaled, I cried, I let myself remember. When I could finally tolerate the computer, I started writing memories. Day after day, month after month, tears streamed as I wrote. Two years later, I had a manuscript. Since then, I’ve been on the daunting publishing path.

But I still can’t teach. Five years off, I can only tolerate writing for a couple of hours per day. I still need long naps every afternoon. Dizziness remains a constant companion. I can not multitask to save my life.

I’m so grateful to finally be on disability, but sometimes grief overwhelms me. When I drive by an elementary school, I can scarcely breathe. I dream of teaching almost every night. And my garage is still full to the rafters of my teaching supplies. I’m still gathering the courage to tackle those memories.

During one of my dreams, I had an insight about teaching that is helping me make peace with its loss. Instead of feeling like a failure I can think of teaching as a gift that was given to me when I most needed it. Teaching offered me a way out of the cult. It gave me a career that would let me finally use all the talents that my abusers tried to bury. On days when I thought I might lose it under the pressure, my students would hug me, sing or dance with me, write me notes full of love, inspire me with their grit, invigorate me with their zest for learning, and demand to study more Shakespeare. (I have video proof if you don’t believe me!) I was able to nurture those kids as if they were my inner child. The experience was healing and transformative. Teaching brought me back to life after the cult tried to extinguish my light.

With this new perspective, I can bear the grief a little better. I can treasure the memories and be proud of the contribution that I made. And maybe, by writing about my experiences, I can use my pain to teach in a new capacity.

I hope my story can be a cautionary tale. If you’re racing through life, trying to outrun your trauma, don’t be surprised when it catches up. Also, keep in mind that certain medications could make matters worse. At best, they’re a band aid. At worst, they can derail your entire life.

You have been warned.